This week’s blog post is late, the first delayed post since the beginning of the Roman Quarantine in March. I have no excuse other than that this is the most somnolent week of the Italian year, and today the most somnolent of all public holidays. It is also the oldest constantly observed holiday in the world: Ferragosto is named for the Feriae Augusti instituted by Augustus in 18 BCE. It morphed into the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin in a lackadaisical Christianisation, but the name remains vehemently Augustan.

During the depths of the extremely strict Italian lockdown, deserted city streets were likened to those of Ferragosto. For evocations of the Ferragosto vibe I heartily recommend Nanni Moretti’s film “Caro Diario”, and the excellent “Il Pranzo di Ferragosto” (translated into English as Mid-August Lunch, rather as if A Christmas Carol were translated as “Late December Song” for a Shinto audience).

I haven’t been in Rome at Ferragosto since 2001. I had then just begun working for a tour company and had a few hours of work and a sense of duty which kept me in town. Everyone I knew was on a beach somewhere, it was a billion degrees, and literally everything was closed, the city weighed down by torpor. Plus––astonishing as it seems––I had no internet access, only a shortwave radio. For a week I reread the novels I had, listened to the World Service, and talked to no-one at all. There was an almost delicious melancholy to it, though I’m not sure I thought that at the time, and it was not an experience I have since sought to repeat.

For many years now I have spent Ferragosto in a rather more Italian manner: on the Ionian coast of Basilicata in the instep of the boot. Ferragosto is spent on the vast and uncrowded beach under an umbrella, before a mammoth feast of barbecued fish under the pergola of vines and citrons in the garden of dear friends.

The early history of this area is intriguing and evocative and is mentioned by a battery of ancient historians both contemporary and not: long after the events he describes, Strabo says the area of Siris was occupied in the distant mists of time by refugee Trojans who brought with them the cult of Athena Iliaca.

Herodotus tells that in the mid seventh century BCE a group of Ionians, resident at Colophon in Asia Minor, fled here to escape the tyrannical King of Lydia, Gyges. He says that these Ionians sacked the Trojan city and founded Polieion. According to Strabo, the statue of Athena closed her eyes lest she witness such violence.

Siris swiftly became prosperous, as is recalled by the poet Archilocus of Paros and writing considerably later, on the cusp of the second and third centuries CE, the erudite Athenaeus speaks of the luxurious clothing and the wealth of the people of Siris nearly a millennium before, who he compares to the nearby Sybarites.

The area’s flowering was brief, and the city was destroyed in the mid sixth century BCE by the Achaean coalition made up of the colonies of Croton, Sybaris, and Metapontus. The Achaeans are said to have slain the people of Siris in the temple of Athena, in grim echo of the violences visited by the Ionians upon the descendants of Troy a century or so before.

Yesterday I engaged in one of my favourite Mediterranean activities: driving down unlikely dusty roads buzzing with the chattering of cicadas and lined with prickly pears to visit a deserted archeological museum crammed with artefacts that no museum in the world would turn down.

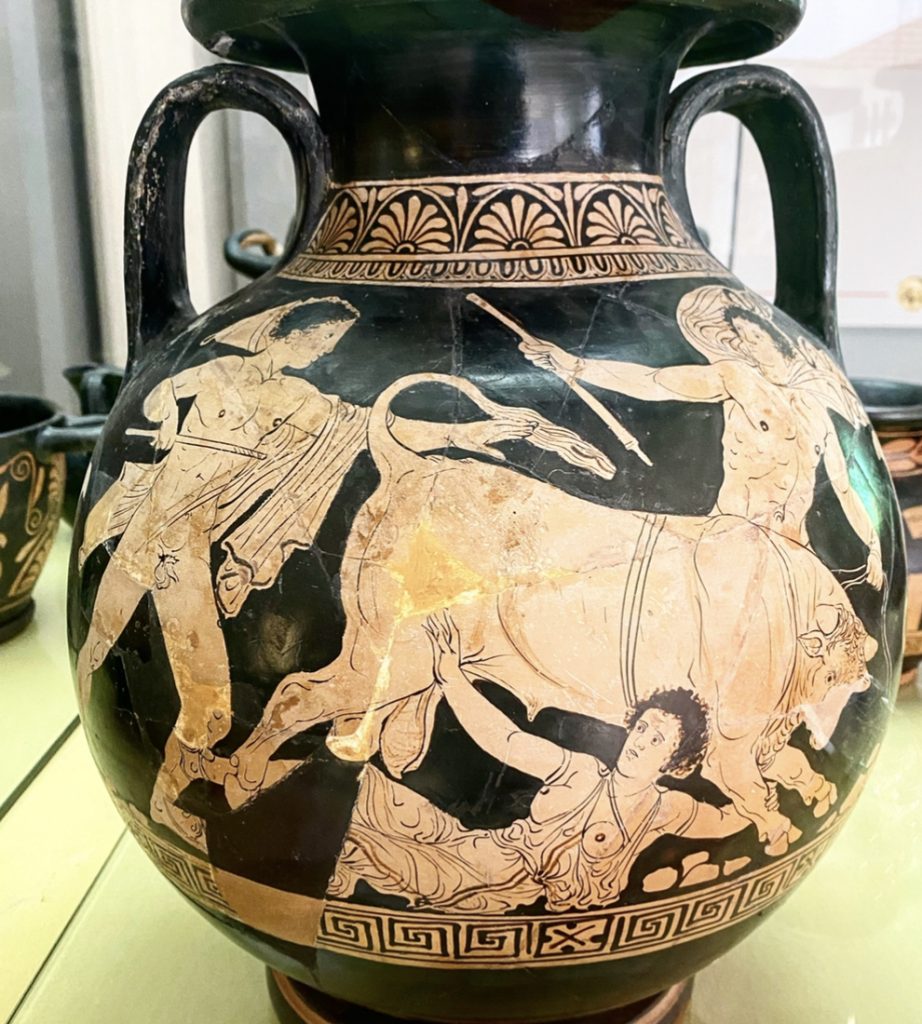

At the Museo Nazionale della Siritide, I admired the extraordinary and rich collection. Amongst much else: vases painted in the early fourth century BCE by the Policoro Painter, ancient jewellery of various periods, and an eighth century BCE deity of the Oenotrian people curiously in the guise of a surprised bear.

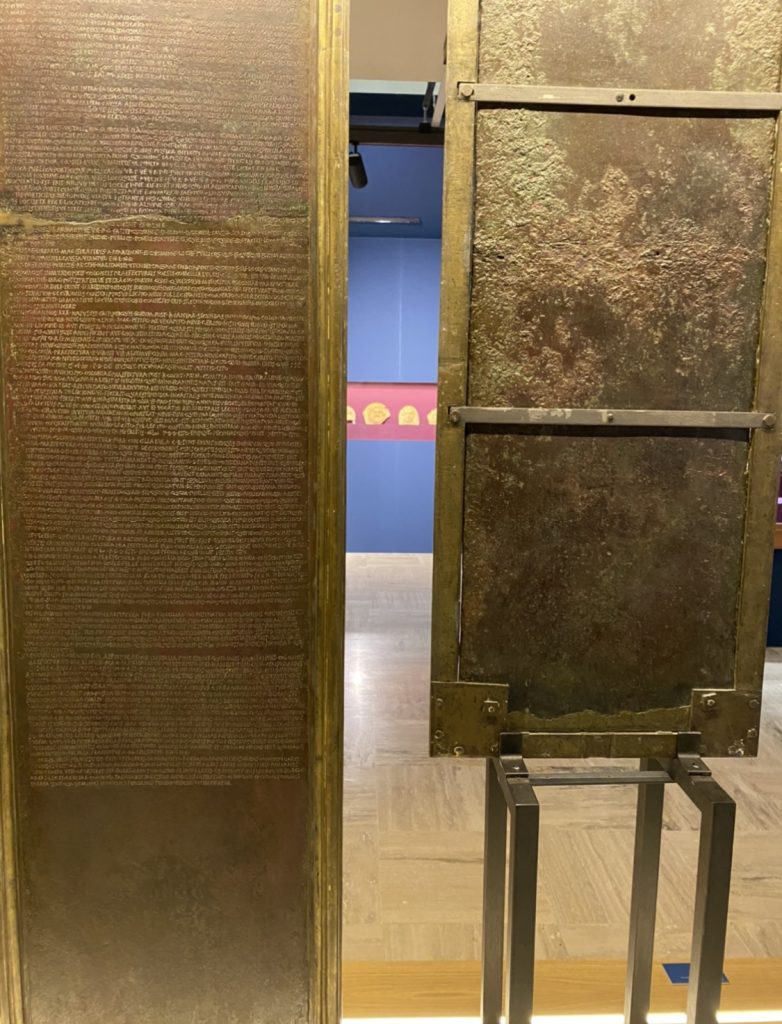

Oh, and the Heraclean Tablets––bronze sheets inscribed in Greek in the fourth century BCE and on the reverse in Latin of the first century BCE (this last an important source for the study of Roman law)––were on loan from the Archeological Museum in Naples, for a visit back where they were found. An excellent museum, and I was the only person there.

We too were in Rome for Ferragosto 2001! Our first visit to the Eternal City

What a delicious piece of writing! Enjoy!

thank you!

Synchronicity behold, we’ve been planning our 2021 trip to the motherland for a awhile now to Matera and Basilicata, and there you are! Will keep you posted and be asking for suggestions as we get nearer.

please do! I’ve been going there for years! v best, Agnes