I mentioned mosaics in the wilder reaches of the Venetian lagoon yesterday. I’ve no idea when I’ll be able to get on a train to Venice, but there are plenty of mosaics in Rome to sate my thirst for multitudes of tiles glittering in the shadows of solemnly silent churches.

If the mosaics of Venice see the Roman decorative tradition filtered through the prism of Byzantium in the service of Christianity, the oldest of Rome’s major Christian mosaics is a direct successor to earlier Roman musive decorations. It is found at the church of Santa Pudenziana, a mere 25 minute walk from my neighbourhood, and is now the church of Rome’s Filippino community (Pudenziana was declared patron of the Philippines by the Conquistador Miguel López de Legaspi). She is a poorly documented figure, who may or may not have existed. Tradition says that she was the daughter of a Roman senator called Pudens, who is said to have harboured St Peter at his house on this spot. Nearly a century after Peter is said to have stayed here (c. 60 AD), the house was replaced by a bath complex, which was itself subsequently partially incorporated into the basilica.

Despite major and multiple remodellings in the intervening sixteen centuries, the church’s ancient foundation is attested to by the fight of steps which leads one significantly below the nineteenth century street level.

Once inside, the apse mosaic beckons. It dates to the church’s construction under Pope Innocent I (402-417) and offers a glimpse into the very origins of Christian art. If earlier Christian decorations had been largely restricted to funerary chapels in the catacombs and sarcophagi, commissioned by relatively humble patrons, the decree of Theodosius of 380 saw Christianity declared the only religion of state. This marked a major shift in every aspect of Roman culture, including art: patronage was now in the hands of the very wealthy, and the expensive art of mosaic was at the disposal of a Church which now had an institutional role.

Christ is enthroned in the centre of the scene. He wears a toga of gold and purple, both colours associated with Imperial power, and is shown bearded. This marks a dramatic departure from earlier depictions (such as the Good Shepherd at the catacombs of Sts Peter and Marcellinus) where Christ is a fair, clean shaven, and youthful figure. Here institutional recognition of the Church sees him imbued with a new gravitas.

The scene appears to be set in the atrium of a grand Roman house. With his left hand Christ holds a book, on which is inscribed “DOMINUS CONSERVATOR ECCLESIAE PUDENTIANAE” (Lord protect the church of Pudenziana), while his right hand is raised in a gesture of benediction. Six apostles are seated on either side, robed in the togas of Roman noblemen and senators.

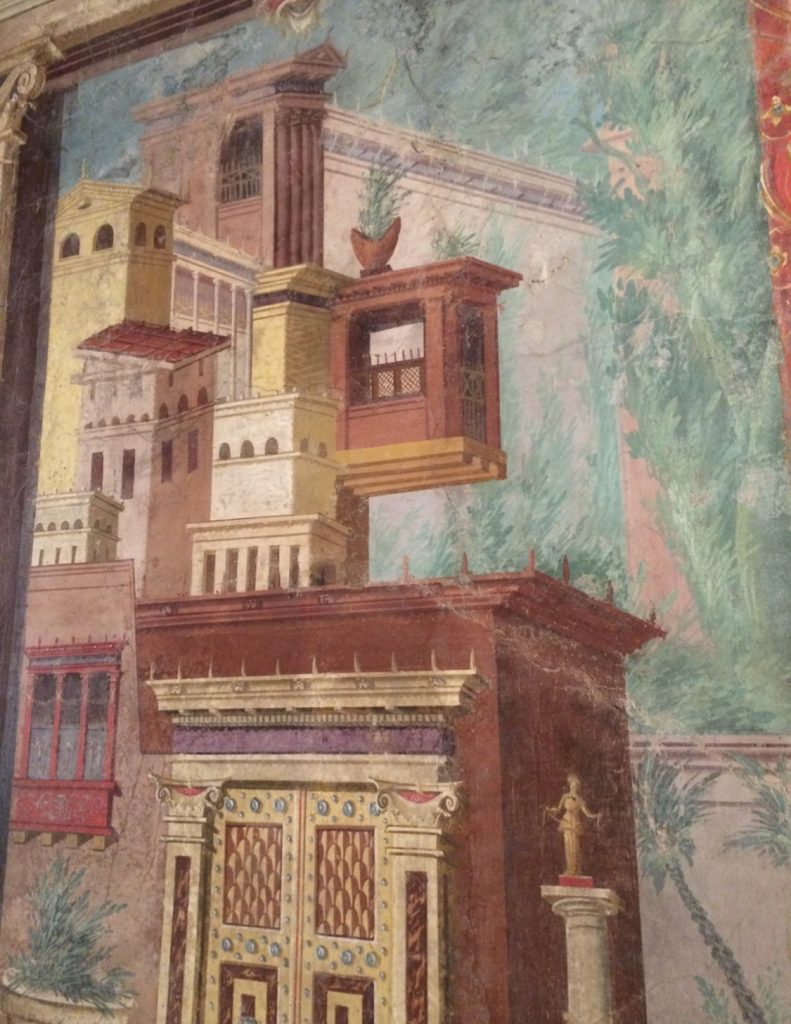

The faces of the women follow faithfully in the expressive tradition of Hellenistic art, the flush of their cheeks, the parting of their hair and the generous folds of their robes tangible in their realism. In the background the roofs of a Roman cityscape stretch into the distance, just the kind of view which would have been seen on the walls of the villas of the Roman haut-bourgeoisie, for example the fresco above from Boscoreale, near Pompeii, now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York City.

This lower part of the scene could show an orator instead of a god. The discussion might be one of earthly legislation instead of the divine. The language and hierarchy of Roman art has been transplanted in the service of the new religion of the State. However, look up and the mystical nature of the subject matter is clear. Above Christ a jewelled cross floats amid fiery clouds, itself a bombastic symbol of triumph, another thoroughly Roman concept. On either side, heavily damaged by later remodelling, are the winged symbols of the evangelists; this is no earthly Imperial cityscape, we are told, this is the new Jerusalem.

Recent Comments