My Instagram account shows that today I had lunch, and then I had dinner. And that was about it. On either side of these events I mostly sat on the terrace and read the letter written to Leo X and attributed to Raphael and Baldassare Castiglione (for an English translation see the appendix of Palladio’s Rome, the excellent, edited translation of Andrea Palladio’s guides to the churches and antiquities of Rome first published in 1554. Thanks Dad!).

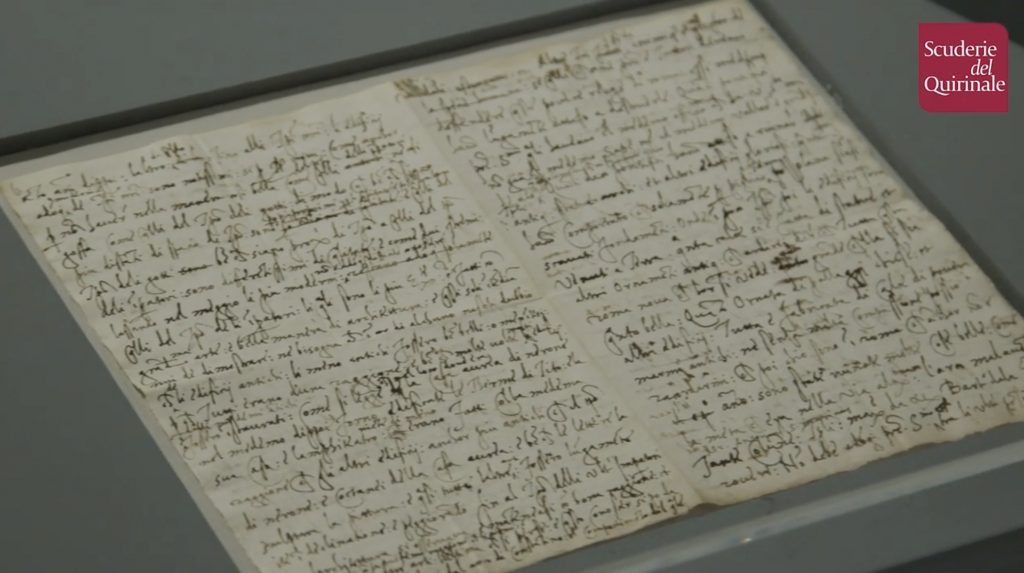

Written in 1519, a year before Raphael’s death, the letter – intended to serve as the dedication of a collection of drawings of antiquities to the Pope, rather to be sent through the post – begins with an appeal to Leo X to map and preserve the buildings of the city. Raphael proposes an ambitious architectural drawing of all the ancient buildings of the city, not as he saw them in the early sixteenth century, but at the height of their splendour during the Empire. An extraordinary project which would be thwarted by Raphael’s death the following year. Even were Raphael not to have succumbed when he did, I find it doubtful that the project would have outlived Leo X’s reign which ended with his death in 1521, but that’s another question. Though the project would remain forever incomplete, the proposal was the most extraordinary and far-sighted idea: an appeal for the conservation of cultural heritage and the built environment five hundred years ago; a desire to immortalise the grandeur of the achievements of the Ancients.

It’s full of great phrases, but perhaps my favourite is at the very beginning:

“Most Holy Father, there are many who, on bringing their feeble judgment to bear on what is written concerning the great achievements of the Romans—the feats of arms, the city of Rome and the wondrous skill shown in the opulence, ornamentation and grandeur of their buildings— have come to the conclusion that these achievements are more likely to be fables than facts. I, however, have always seen—and still do see—things differently. For, bearing in mind the divine quality of the ancients’ minds as revealed in the remains still to be seen among the ruins of Rome, I do not find it unreasonable to believe that much of what we consider impossible seemed, to them, exceedingly simple.”

It reminded me of all of those absurd “theories” about the Egyptian pyramids being built by aliens. Only vaguely aware of such things, I’d always assumed them a joke (ditto the Flat Earth people). It turns out, sadly, they’re not. There are really people who believe that human ingenuity could not have built the Pyramids, or Machu Pichu, or the Great Wall of China, and that they are more likely to be the work of aliens than that of ancient people of civilizations distant from our own (these “theories” are often given a racist bent, too). I like to think this would’ve set Raphael’s beady black eyes aflame and, his tongue sharpened with wrath, he would have had much to say about the myopic limitations of “bringing… feeble judgement to bear” and “com[ing] to the conclusion that these achievements are more likely to be fables than facts.”

It is fitting that – even if no one can see it at the moment – five hundred and one years after it was written, this letter is today right next to the Quirinal Palace, seat of Italy’s head of state, the President of the Republic: Raphael’s eloquent appeal for the survival of the memory of the city’s ancient buildings – this extraordinarily avant-garde plea for architectural conservation – is a sentiment which finds its way into Article 9 of the Italian Constitution which states:

“The Republic…safeguards the landscape and the historical and artistic heritage of the Nation.”

He was a far-sighted fellow, Raphael.

Recent Comments