Today is the twenty-eighth day of the Roman quarantine. Exactly four weeks have passed since the extraordinary announcement of the shutdown. When I started writing these posts we here in Italy were in an anomalous situation. Now most of you are in a very similar boat, and as I write the UK Prime Minister has been admitted to Intensive Care. This all feels like it’s going alarmingly even further into uncharted territory. There is however a glimmer of light: in Italy, the effect of the lockdown is now seeing a significant decline in numbers of those who are seriously ill. How we emerge from this situation is, however, far from clear. Slowly, I suppose, and by putting one foot in front of the other, taking each day as it comes, and other cliches which are strangely comforting.

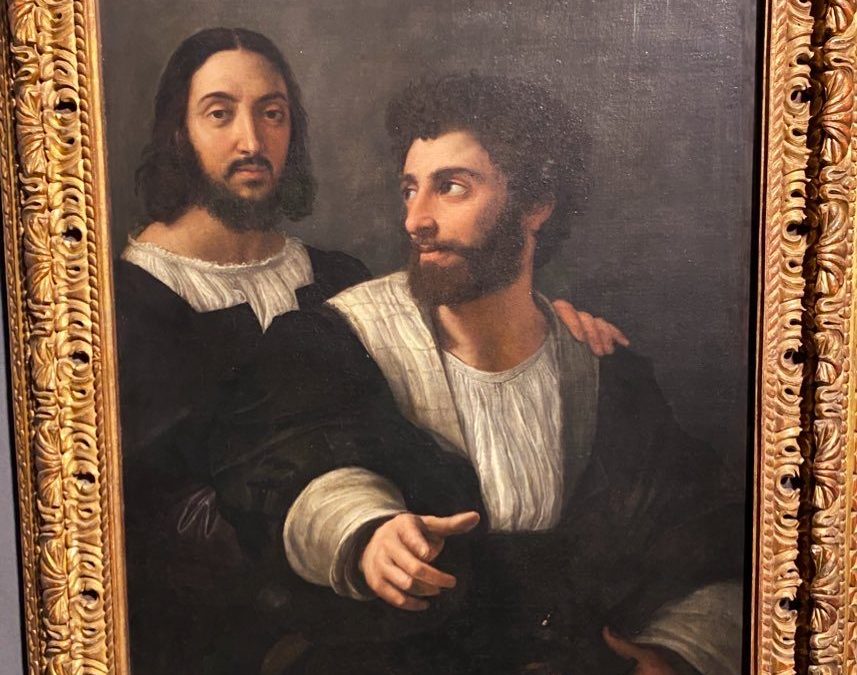

This limbo has done very odd things indeed to time, and the erratic and claustrophobic temporal hall of mirrors we are all caught in can, I find, be alleviated by looking far into the distance. It just so happens today is a very important anniversary, so that’s as good a distant point as any. Five hundred years ago today, on 6 April 1520, eight days after developing a fever Raffaello Sanzio died (sorry I can’t take your mind off this entirely; illness is a universal constant). He was thirty-seven years old. This may also have been his birthday, though – like Shakespeare who is also often believed to have been born and to have died on the same day – his birthdate is a little hazy. Whether in late March or early April of 1483, he was born in the town of Urbino. The year before Raphael’s birth Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino had died. He was to be described in Baldassare Castiglione’s handbook for Renaissance courtiers, Il Cortegiano (1528), as “in his day, the light of all Italy”. It was of course serendipitous that Raphael should be born the son of a court artist and poet, in the “little city of Urbino”: his talent fell on fertile ground. Had he been born in a different moment or place, perhaps 50 miles inland and 50 years earlier, he would doubtless have become an excellent baker, or wheelwright, or blacksmith. As it was he was born in Urbino immediately after the reign of Federico, and he became the best painter in the world.

Four days before the Italian shutdown on the evening of 9 March, the long-awaited major exhibition to commemorate Raphael’s death had opened at the excellent Scuderie del Quirinale (to my mind the only exhibition space in Rome which consistently produces world-class shows). It just so happened I went. We were due to have been travelling to Dublin that Thursday, to see friends and the Six Nations Rugby game. The game was cancelled but no travel restrictions were suggested for anywhere other than the worst hit Northern Italian areas. Nevertheless we decided it would be irresponsible to risk travelling to a country without infections at the time, perhaps inadvertently causing harm, and regretfully cancelled our trip at the last minute.

So it was that on 5 March, the day of the opening of the exhibition, I was in Rome. On a whim I went and stood in a strung out queue for half an hour, not because it was extremely busy (owing to the situation, it wasn’t) but because numbers were being extremely heavily restricted to ensure distance could be maintained inside.

I only had a couple of free hours and so concentrated on the first floor, assuming I’d come back the following week for the rest. In fact it was only open for three days: on the morning of Sunday 8 March all Italian museums were closed (about which I wrote this). Those extraordinary paintings hang in dark and empty rooms, and we have only to look at photographs of them when we recall “the divine” Raphael, a genius who succumbed to a tiresome and banal virus five hundred years ago today.

Very interesting thank you for taking the time to share these.

thank you for reading, and for taking the time to comment. Much appreciated!

I love your posts. I have friends and family in Italy and especially Roma. Your historical posts fascinate me.

Thank you

Thanks!