The first version of this post was written for the fabulous, but now sadly defunct, 3 Pipe Problem blog. It was run by the fearsomely energetic Hasan Nayazi who died suddenly and prematurely last year. I met him in person once, on his only visit to Rome two years ago, and I had the great fortune to visit the Villa Farnesina and the Vatican Museums with him, retracing the steps of his hero, Raphael.

Piranesi’s elevation of the site at Sant’Agnese fuori le mura, showing the mausoleum of Constantina and the buttressing of the Constantinian basilica of St Agnes

On the via Nomentana, two miles outside the walls hurriedly thrown up by the Emperor Aurelian between 271 and 275, is the place where the young martyr Agnes is believed to be buried. Her life (and death) is one of myth and contradiction. Tradition says she was executed following her refusal to marry a Roman nobleman. Whether this took place during the furious mid-third-century persecutions of Christians ordered by the Emperors Decius, Gallus, or Valerian, or perhaps those of Diocletian at the very beginning of the fourth century, is uncertain. These doubts notwithstanding she is a key figure in the early church, the Depositio Martyrum of 336 referring to the celebration of her feast day; the “XII Kal. Feb. Agnetis, in Nomentana”. She is clearly also a favourite of St Ambrose, who lauded her in his De Virginibus (337), his De officiis of c.391, and to whom the hymn “Agnes Beatae Virginis” is attributed.

The circus basilica of St Agnes on the left, the mausoleum of Costanza on the right. (image courtesy of prolocoroma.it)

The Emperor Constantine’s legalization of Christianity, with the edict he issued at Milan in 313, saw a spate of church building in the capital. A series of “cemetery basilicas” were built close to the burial areas of the early martyrs. Often described as “circus-shaped”, they evoke the shape of the Roman race-track, rectangular at one end, semi-circular at the other (apse) end, with an ambulatory running around the edge. The floors of these basilicas contained large numbers of tombs on several levels, with the burial areas closest to the believed places of the martyrs being especially in demand. Sadly these cemetery-basilicas do not survive intact, but fragments of the fourth-century basilica of Saint Agnes (replaced by a nearby church in the seventh century) can still be seen, its scale especially visible from the modern piazza Annibaliana where buttressing supports the significant earthworks which had created the terrace from the hillside.

The Liber Pontificalis (the book of papal biographies said to have been begun by St Jerome, but certainly later in date) refers in a sixth-century note to the church of St Agnes which it says was built by Constantina, daughter of Constantine. It speaks of Constantina “who is devoted to God and Christ [and] has with all humility taken all costs [for the building] upon herself and … dedicated this sanctuary to the victorious virgin Agnes”. The land on which the basilica was built was Imperial property, and Constantina also commissioned the construction of her own mausoleum here, abutting the long side of the basilica of St. Agnes and originally connected to it by an apsidal porch. The building of a mausoleum attached to a cemetery-basilica was not without precedent in the Imperial family; Constantina’s father Constantine had himself been buried in a mausoleum attached to the Basilica of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, as had his mother Helena at the Roman basilica of Saints Marcellus and Peter on the via Labicana.

The mausoleum was probably begun following the murder of Constantina’s first husband, her cousin Hannibalianus, King of Pontus and Cappadocia, in 337, and before her marriage in 351 to another cousin, Constantius Gallus. Modifications to the original modestly sized trefoil plan saw it enlarged, befitting a mausoleum for several members of the Imperial dynasty, and given the circular form we see today. These changes are believed to have taken place after Constantina’s second marriage, and before the death of her brother Constantius, probably the sponsor of the project, in 361. The fourth-century historian Ammianus Marcellinus speaks of Constantina’s body being buried on the Imperial property outside the city walls on the via Nomentana following her death in Bithnya in 351, when she would have been about forty years old. He also tells us that Constantina’s sister Helena was buried here in 360, further evidence that the grander scale of the mausoleum was designed with members of the family other than Constantina in mind.

The building was certainly used as a church by the mid-ninth century, and in 865 it is referred to as a church dedicated to Saint Constance. If we are to believe the Liber Pontificalis, Constantina appears to have been a Christian, an interpretation absolutely supported by the location of her mausoleum. However there is no evidence whatsoever for her canonization, and she is no longer recognized as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church. Nevertheless it is the mausoleum’s consecration as a church, in great part the product of the confusion surrounding the figure of Constantina, which is at the heart of the building’s survival; as a church it was not only deemed sacred but was simply in use and thus not subject to the same levels of looting of materials that befell other structures.

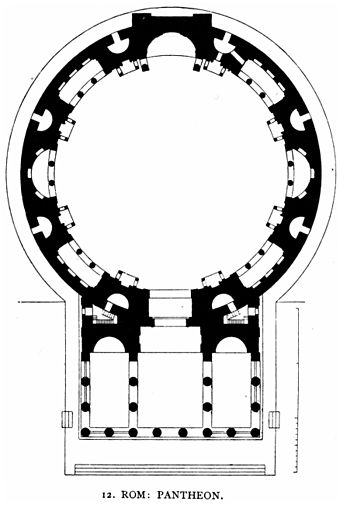

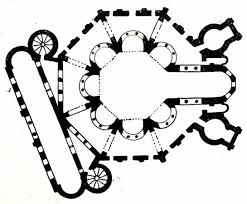

The building is circular, 22.5 metres in diameter, with a central concrete dome resting on a clerestory above a ring of twelve pairs of columns with composite capitals. That these capitals are not exact matches, and were “recycled” from earlier structures belies the decline that Rome found herself in. Some two decades after Constantine had founded Constantinople as his new administrative capital in a desperate bid to reclaim control of the fragmenting eastern provinces, the Caput Mundi was feeling the strain. Most of the illumination which is such an important part of the building is provided by twelve windows set into the drum of the dome, one above each of the arches. The ring of columns is surrounded by a barrel-vaulted ambulatory with fourteen niches inset into the exterior wall. Originally a colonnaded portico (which no longer survives) ran around the exterior wall. Like the portico around a classical temple it did not offer access to the interior, but rather served both structurally as an additional support (in this case for the concrete dome), and ideologically as a buffer zone between the worldly and the sacred. Also now missing is the entrance porch which archeological investigations have revealed, like that of the early fourth-century temple of Romulus in the Roman Forum, to have been convex in form.

The mausoleum of Constantina can be seen as heir to a long tradition of centrally-planned funerary structures. Circular and conical forms are among the most archaic (piles of stones to mark an important location; the huts of the Bronze Age). This atavistic architectural impulse, coupled with the elegance of the circular form, and its innate connotations of the infinite, led centrally planned buildings to become associated in a Christian context not only with martyria but also with baptisteries.

Two centuries after the construction of the Pantheon, at the mausoleum of Constantina we witness an important moment in the development of the centrally-planned building. The study of the floor plans of the buildings along this journey can be viewed as stills from a time-lapsed film of biological development. We begin with the purely cylindrical (tumuli, Cecilia Metella) before the space gradually opens out (Mausoleum of Hadrian), and begins to be alleviated by a series of niches (reaching its apotheosis at the Pantheon). These niches then continue to reach outwards, breaking through the perimeter wall like buds on a dividing cell. They leave behind the dots of columns which trace the original cylindrical form and support a vaulted ambulatory around the domed central space. This ambulatory (which one can consider as a sort of circular aisle) is a new development in Roman architecture, and its earliest surviving form is seen at Santa Costanza.

Through this organic development a structure develops in which, as in nature, every element works together as part as a coherent whole. Like all great buildings it is governed by its past, but is also charged with a present which both defines and enriches it.

The mausoleum of Constantina thus heralds a key point in the ever greater ornamentation and dilation of space which paves the way for the centrally-planned place of Christian worship, as would be seen at the rotonda of the Anastasis at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jersualem (dome completed late fourth century), and at San Vitale in Ravenna (completed 546).

When Bramante created what is now seen as the first building of the High Renaissance over a millennium later, the Tempietto of San Pietro in Montorio, he turned once again to the harmony of the central plan.

Mausoleum of Constantina (Church of Santa Costanza)

Sant’Agnese fuori le mura

Via Nomentana 349

9am-12noon; 4pm-6pm (unless religious services are taking place. Saturdays in June are best avoided as it’s a favourite for weddings)

Trackbacks/Pingbacks